The real ballad of Frankie Silver, one of the first women executed in North Carolina

Frankie Silver was the first white woman executed in North Carolina. Here’s the real story of what happened to her back in the 1830s.

Her story is one of folkloric legend. At 18 years old, Frances “Frankie” Silver was accused of murdering her husband, Charles “Charlie” Silver, and was sentenced to death for her crime. Roughly two centuries have passed since then, and the details surrounding what really took place that fateful evening in 1831 have become both clearer and more clouded. We have a better understanding now as to why Frankie was driven to murder, and how she was convicted despite a lack of evidence proving her guilty beyond a shadow of a doubt. However, sifting through the remnants of the past can still leave plenty of room for confusion.

Tales were told about how Frankie sang the lines of a poem she had written right before she was executed in Morganton, in which she confessed to her crime. “Frankie Silver’s Confession” became the foundation of her myth—one that grew alongside the expansion of time until it transformed into a version of the truth that was commonly accepted for decades. Stories, books, and plays were written about Frankie’s confession, including Sharyn McCrumb’s 1998 novel, “The Ballad of Frankie Silver,” the title of which I’m borrowing for this piece, but with a slight twist. It wasn’t until more recently, though, that the origins of Frankie’s confession were finally uncovered, revealing just how deep the mysticism of her ballad ran.

Even though the account of Frankie’s guilt—and her reported poetic confession—have melded together to create a new narrative over time, many of these details are based more in fiction than they are in fact. Like any story told and retold over nearly 200 years, some of the information will always remain a mystery. Frankie didn’t confess to killing Charlie, and she wasn’t allowed to give her testimony in the courtroom, as women weren’t permitted to do so in the 1830s. She never told her lawyer or the judge assigned to her case what really happened. When Frankie Silver walked to the gallows in 1833, her father, Isaiah Stewart, reportedly called out from the crowd, “Die with it in you, Frankie.”

And so Frankie did.

Three days before Christmas, 1831

While researching the case, it became abundantly clear that it’s a genuine fact that Frankie Silver murdered Charlie Silver three days before Christmas in 1831. Some journalists and historians indicated that Frankie took an axe to her husband in a fit of jealous rage. I couldn’t find anything to support this theory of infidelity, but the most commonly held belief is that she was driven to an act of irreversible bloodshed because Charlie had a history of violence himself. Fellow Kona, North Carolina residents believed that Charlie repeatedly abused his wife, and the clerk of court, B.S. Gaither, said there was strong evidence to support this inkling.

Based on this alone, it’s easy to see why Frankie may have had enough of Charlie’s behavior and chose to take matters into her own hands. As Wayne Silver, a family historian, told Blue Ridge Country in 2001, there was reportedly more to the story than that. Wayne said that Charlie reportedly went out to buy the Christmas alcohol and decided to sample the stock on his way home. He was 19 years old at the time. When Charlie got back, Frankie supposedly started complaining, and their baby daughter, Nancy, was crying. This, according to Wayne, is when “things turn ugly.” Charlie allegedly picked up his gun and yelled, “‘So help me Frankie—if you don’t shut up, I’m going to shoot the both of you!’”

Wayne said that “He [Charlie] probably didn’t mean it. But by this time Frankie had picked up the ax.” She allegedly told Charlie that she wouldn’t let him hurt her anymore, and that she wouldn’t let him hurt their baby. She swung the ax at her husband, and depending on whose account you put your stock into, she swung it a few more times for good measure. Wayne didn’t think it was a premeditated murder, and he stated that the Silver family always believed “it was more of an accident than anything else.”

The aftermath of the murder, though, may have been more calculated than it was accidental.

Evidence and accusations

Frankie is said to have told people in town that her husband was missing. She was frightened—both of what she had done, and of what would likely become of her if anyone was to discover her crime. Reports vary as to whether her mother, Barbara, and her brother, Blackston, helped her kill Charlie, or if her family simply helped her dispose of Charlie’s body in the aftermath of Frankie’s attack. According to Blue Ridge Country, a man named Jack Collis was the first to suspect that there was something seriously wrong at the Silver house. He searched the property one day while Frankie was out and discovered bone and ashes in the fireplace, along with a pool of blood under the floorboards. The details are more gruesome than that and aren’t for the faint of heart, but if you’d like to read more, you can do so here.

Once Charlie’s remains were discovered, Frankie, Barbara, and Blackston were all arrested on January 9, 1832, but as the UNC University Libraries states, “only Frankie was indicted for the murder.” Frankie’s father, Isaiah Stewart, “obtained a writ of habeas corpus, saying that his wife, daughter and son were being illegally detained.” After Isaiah presented this, the charges against Blackston and Babrara were dropped, but Frankie remained behind bars. The charges against her mother and brother would be formally dismissed on March 17, the same day Frankie was formally indicted on a murder charge.

Many of those who look at this situation in hindsight are confused as to why Frankie’s lawyer didn’t try for a self-defense charge, given that there was evidence to support the idea that Charlie had been abusive toward his wife for some time prior to his death. As Blue Ridge Country put it, her lawyer and father thought it was best to have her plead not guilty, thereby forcing the state to prove her guilt. This seemed, at the time, impossible to do due to the lack of physical evidence proving she had been the one to swing the axe that night.

The intricacies of Frankie’s 1832 trial are complicated and confusing, and for the sake of time, I’m only going to go over the broad strokes version of what happened. If you’d like to wade into the weeds of the legal aspects of the trial, including how the all-male jury sealed Frankie’s fate, click here. Essentially, testimony from witnesses varied greatly between one day and the next. On the first day, the jury was deadlocked at 9-3 in favor of acquittal. By the next day, they unanimously found her guilty. Her case was appealed to the North Carolina Supreme Court almost immediately, but without success. Frankie was then scheduled to be executed during the 1832 fall term of the county court, but the judge didn’t show up, so her execution was scheduled during the spring of 1833 instead.

Frankie was, eventually, sentenced to be executed in Morganton on June 28, 1833. She escaped from prison on May 18 with the help of her father, uncle, and potentially some insiders, as “90% of the community now wanted Frankie spared.” She was caught a few days later at the Tennessee border and returned to jail. The governor postponed the date of her death for two weeks, as there were petitions to save her from the gallows. The petitions, along with the community’s outrage, unfortunately didn’t amount to anything in the end.

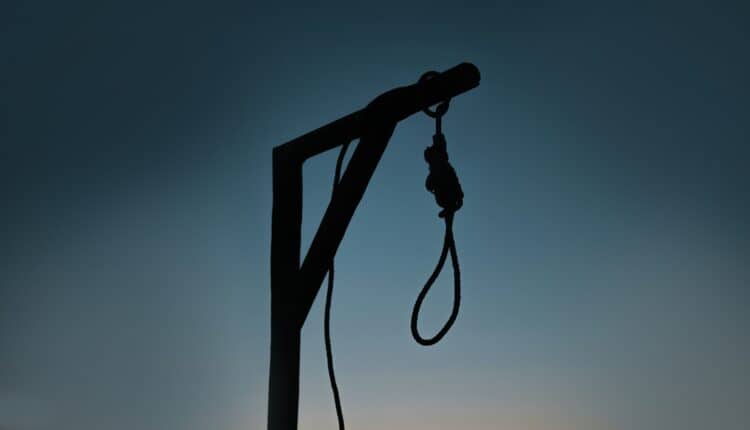

Frankie Silver was set to die on July 12, 1833. The people in the crowd that day likely had no idea of just how mythic Frankie’s life would become after she made her way to the gallows and out of this world.

The gallows and the ballad

Legend has it that 18-year-old Frankie Silver approached the gallows in Morganton with her head held high. Before she was hanged, she reportedly sang the lines of a poem she had written, and, at long last, confessed to her crime. “Frankie Silver’s Confession” was retold numerous times over the years by local historians, journalists, and storytellers. And while the idea of Frankie’s ballad does make for an impressive story, it isn’t actually true. According to UNC, “This ‘Confession’ was not penned (nor sung) by Frankie Silver after all. After several lengthy investigations by historians into the origins of the song, a consensus has emerged that it was written by a man named Thomas W. Scott, a school teacher who lived in Morganton at the time of the execution.”

It appears as though this moment in North Carolina history was the product of a prolonged game of telephone—one that was passed along so often, and with such fervor, that the truth became lost in the retelling. What really happened on July 12, 1833, is this: Frankie Silver did climb up to the gallows with her head held high, and her father did reportedly call out to her from the crowd to die with the truth inside her, and that’s exactly what Frankie did. Isaiah Stewart had prepared a coffin, so he could “take her back to her own people,” but he was forced to bury her about eight miles outside of Morganton instead. A stone was finally erected at her place of burial alongside the Old Buckhorn Tavern Road in 1951, though it’s apparently hard to find nowadays.

Many versions of this narrative will tell you that Frankie was the first woman to be executed in Burke County, or in North Carolina, but this is another false element of the tale. Frankie was, by most accounts, the first white woman hanged in the state, but other women of color had been executed before her. That detail is just another layer of storytelling that paints over the real picture that history tried to leave behind.

It’s the perfect example of how fiction is often used to enhance a factual event that would have been just as interesting if the details of what really happened were the ones that had been passed along over the last 200 years. But, as a people, we come from a long line of storytellers, many of whom stretched the truth to ensure the stories they’d witnessed would stand up against the test of time. For Frankie Silver, her immortalization came at the hands of those who fought to free her—who wanted a better future for the 18-year-old girl who was described as “mighty,” and “pretty,” and who was known for her charms. They couldn’t save Frankie from the gallows that day, but they made sure that no one would forget her name. And now, none of us has.

Note: Frankie and Charlie’s daughter, Nancy Silver, was allegedly raised by family members, though it’s unclear as to which side of the family this may have been. Her life, like the lives of her ill-fated parents, seems to have been equally complicated and marked by grief. You can read more about Nancy here.