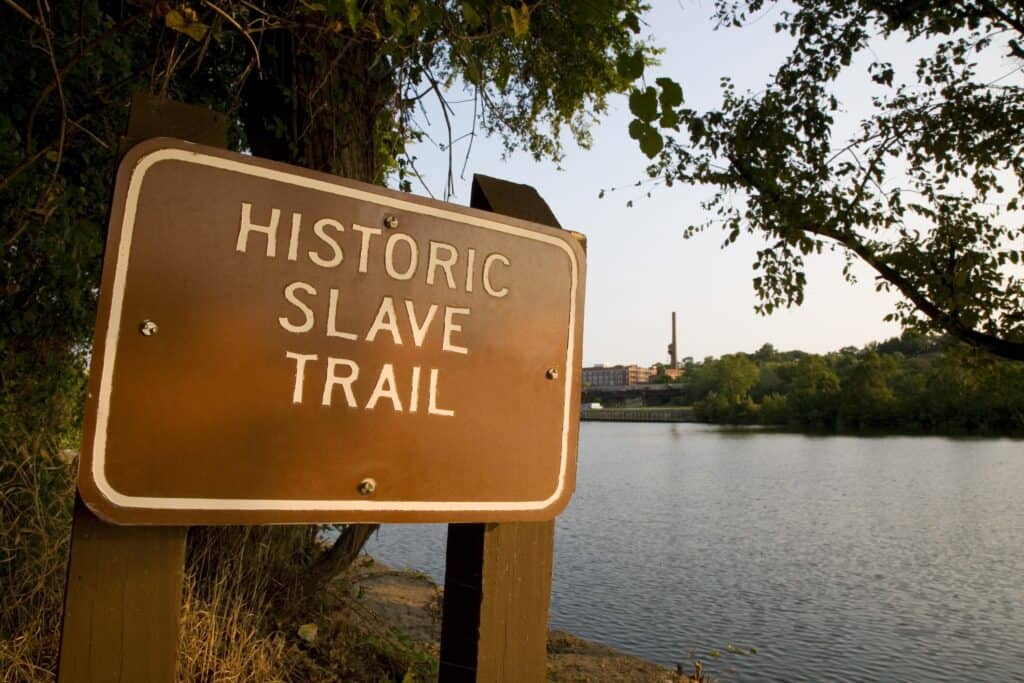

The Richmond Slave Trail follows 17 interpretive markers along the James River, chronicling the city’s past as a slave trading hub.

To recognize Black History Month, consider walking the Richmond Slave Trail. It offers a powerful way to engage with the city’s past through a series of markers. The walking trail begins at Manchester Docks and guides visitors through sites tied to the trans-Atlantic and domestic slave trades, forced labor, resistance, and remembrance. Each of the 17 stops reveals a different layer of the city’s history, ranging from the arrival of enslaved Africans and the mechanics of the sale to rebellions and community building.

History of Richmond Slave Trail

The Richmond Slave Trail is administered through the Richmond City Council Slave Trail Commission, which was established in 1998 to preserve the city’s history of slavery.

The commission has spearheaded several projects over the years, two of the most notable being the 2009 development of the Richmond Slave Trail Marker Program and the 2011 installation and unveiling of 17 markers throughout the East End of the city. The markers tell the story of the journey those enslaved took. Then-Gov. Bob McDonnell attended the unveiling. The speakers, including McDonnell, stressed that the country needed reminders of the past, such as the trail, to avoid repeating the same mistakes in the future.

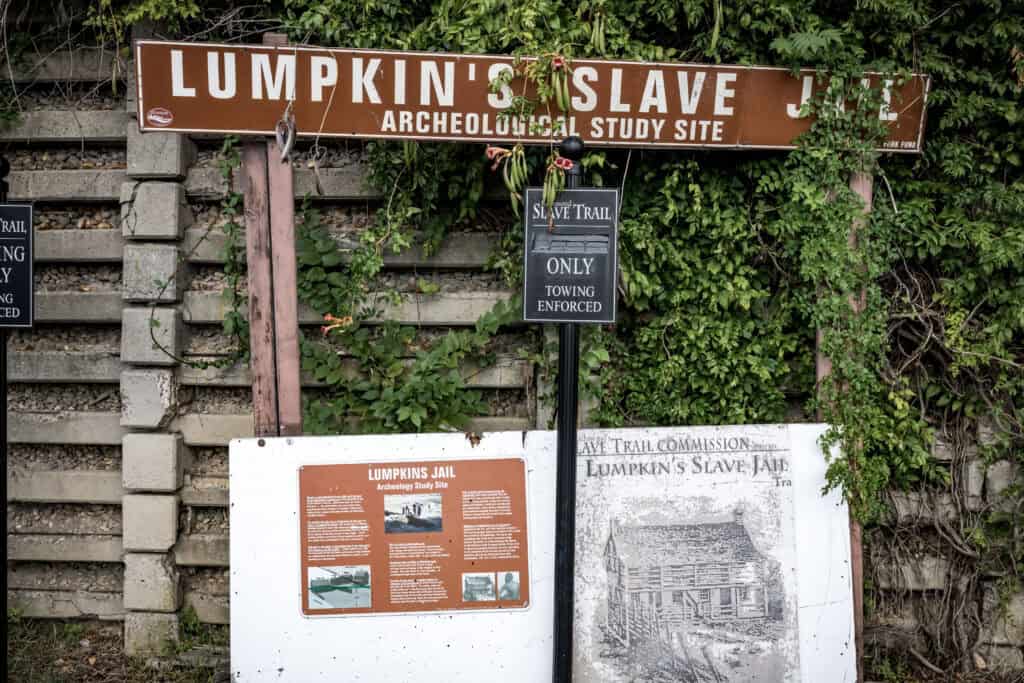

The 2008 discovery of the historic foundation and architectural artifacts from Lumpkin’s Slave Jail was another significant project the commission was involved in.

Richmond Slave Trail stops

The Richmond Slave Trail consists of 17 stops, starting with “Crossing the Atlantic” and ending with First African Baptist Church. The trail can be accessed at Manchester Docks at Ancarrow’s Landing at 1200 Brander St.

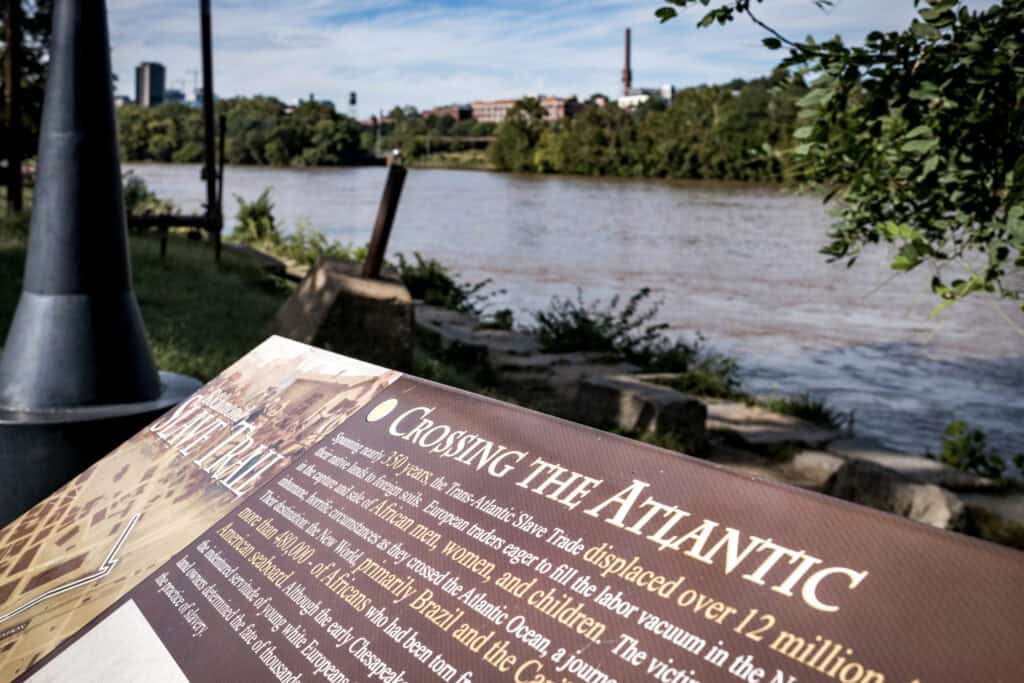

1. Crossing the Atlantic

The first stop, “Crossing the Atlantic,” details how enslaved Africans were transported up the James River prior to 1776 to work in tobacco and wheat fields. Following the 1778 outlawing of the importing of Africans from abroad in Virginia, the Manchester Docks and Rocketts’ Landing were used as “downriver” slave trade ports.

2. Mechanics of Slavery

“Mechanics of Slavery” recounts how enslaved Africans were made to walk along the banks of the James River to nearby towns so that they could be sold upon reaching Virginia. Part of the signage explains how Africans were forced to transition from their homeland to the unfamiliar environment of Virginia.

3. Despair of Slavery

“Despair of Slavery” focuses on how enslaved Africans were handcuffed in pairs with iron staples and bolts. The short chain that connected the wearers alternately by the right and left hand was only a foot long.

4. Creole Revolt

“Creole Revolt” tells the story of the 1841 revolt on the Creole, which was sailing from Richmond to New Orleans at the behest of Richmond traders. During the voyage, Madison Washington, one of the 100 enslaved Africans on the ship, started a mutiny. He redirected the ship to Nassau. Upon arrival, the Bahamas freed the enslaved on the ship.

5. Native Markets

“Native Markets” explains how various Virginia plantation owners and traders purchased an estimated 114,000 Africans over the course of the 90-year Trans-Atlantic slave trade. More than 40% of the imported Africans were brought to the Upper James after 1746.

6. Slavery Challenged

The “Slavery Challenged” stop chronicles the various actions aimed at challenging slavery during the 18th and 19th centuries. In 1782, the commonwealth removed restrictions on the freeing of slaves, which meant that by 1800, 20% of Richmond’s black population was free. However, the General Assembly reacted negatively to Gabriel’s Revolution in 1800 by placing new restrictions on the freeing of slaves. Later in 1808, Congress voted to outlaw the importing of slaves.

7. Richmond’s Burgeoning Trade

The dogged harvesting of tobacco led to the exhaustion of Richmond’s soil by the mid-1800s, as told by the marker “Richmond’s Burgeoning Trade.” This resulted in an overabundance of laborers, who were exported to the Deep South to work on sugar and cotton plantations. By 1840, Richmond replaced Alexandria as the most active exporter of enslaved Africans in the commonwealth.

8. Transitions

“Transitions” charts Manchester’s legacy as a manufacturing center and as a market for enslaved people. The coal and tobacco port merged with Richmond in 1910. At one point, Richmond became the largest slave market north of New Orleans.

9. Mayo’s Bridge

“Mayo’s Bridge” tells the story of how John Mayo built a toll bridge in 1788 to connect Richmond and Manchester. The bridge was regularly traveled by 19th-century enslaved Africans who were being sold to the South from Shockoe Bottom markets. They were often transported in carts across the bridge.

10. Use of Arms

Life for Africans living in Richmond became perilous during the Civil War, as told by “Use of Arms.” Starting in 1864, African men were arrested on the streets by the provost marshal and forced to work to improve the city’s defenses.

11. James River & Kanawha Canal

The “James River & Kanawha Canal” stop explains how enslaved Africans were forced to perform the back-breaking work to build the canal, which was conceived by John Marshall in 1812 to connect Tidewater Virginia with the Ohio River, after the original white Irish laborers who were hired for the job died of hyperthermia. The enslaved were thought to be impervious to the dangerous conditions.

12. Auction Houses

“Auction Houses” notes how Shockoe Bottom auction houses sold human goods, as well as staples like corn and coffee. The selling of slaves was concentrated along a 30-block stretch of Broad, 15th Street, and 19th Street, as well as the river. Portions of Davenport & Co, an auction house in the center of the slave-selling district, survived the Civil War and can still be viewed today.

13. Reconciliation Statue

The British, African, and American triangular trade route is memorialized in the “Reconciliation Statue,” which is identical to ones in Liverpool, England, and Benin, Africa. In 2007, the Virginia General Assembly articulated its regret for the commonwealth’s involvement in the slave trade.

14. Odd Fellows Hall

The “Odd Fellows Hall” stop explains how the hall, which was used for operas and dances, was also the site of many slave auctions during the 1840s-1850s.

15. Lumpkin’s Jail

Robert Lumpkin owned “Lumpkin’s Jail,” a compound that consisted of lodgings for traders, a slave holding facility, and an auction house. “The Devil’s Half Acre” is how enslaved Africans referred to the site. By 1867, the site was rented to a Christian school, a predecessor institution of Virginia Union University.

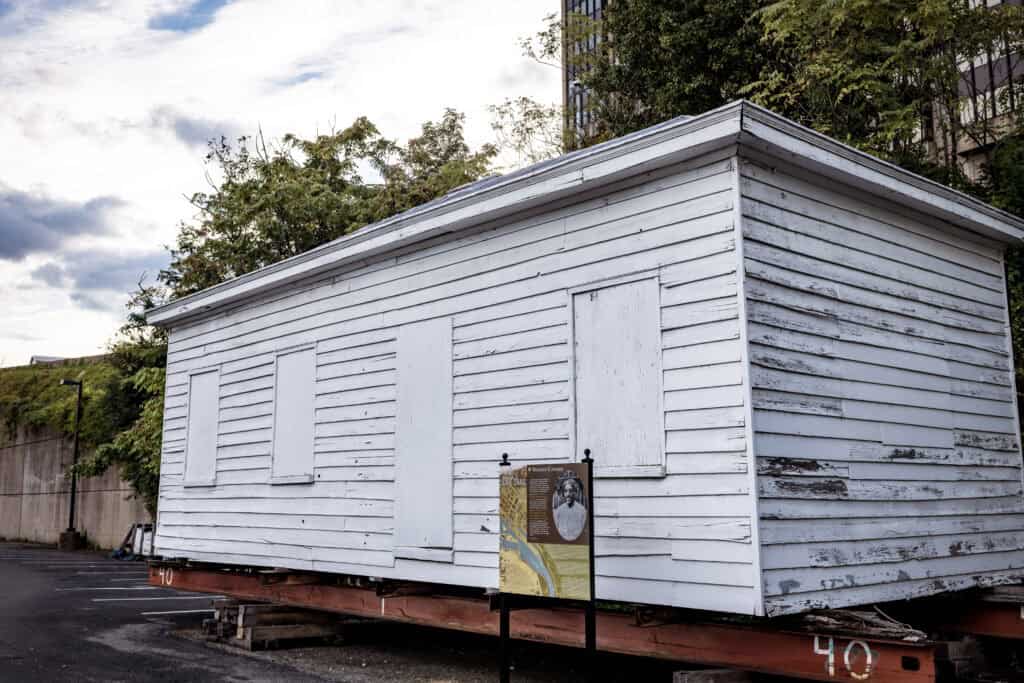

Although it’s not an official stop on the trail, Winfree Cottage is between the 15th and 16th stops. The cottage was likely built in the closing days of the Civil War by David Winfree for his former slave, Emily Winfree. Emily likely lived in one room with her five children that David fathered, while the other room was rented out.

16. Richmond’s African Burial Ground

The “Richmond’s African Burial Ground” stop is where a considerable number of early Richmond residents are buried in unmarked graves. It was the first designated burial ground for those of African ancestry in the city. The mastermind behind Gabriel’s Rebellion is buried at the site.

17. First African Baptist Church

The final stop is at the “First African Baptist Church,” which was established in 1841 following the sale of the building by white members of First Baptist Church to roughly 1,700 African American members, both free and enslaved. The sale price was $6,500. The church went on to become a center for African American community development.