‘Dark tourism’ in Pennsylvania: 7 places to go

By drawing travelers to sites of tragedy, “dark tourism” can create space to connect with history. Here are four examples in Pennsylvania.

“Dark tourism” involves traveling to places associated with tragedy, conflict, or disaster—such as battlefields, once-flooded cities, or old prisons. While the term might suggest nothing more than morbid fascination with the dark side of human nature, many tourists are drawn to these sites to better understand history or reflect on the human capacity for resilience as well as violence. And the impact of such tourism often depends on how a site chooses to present its story: whether it seeks to educate and commemorate, or to commercialize and exploit.

Here are seven dark tourism sites in Pennsylvania, and how you can engage with them without sensationalizing them.

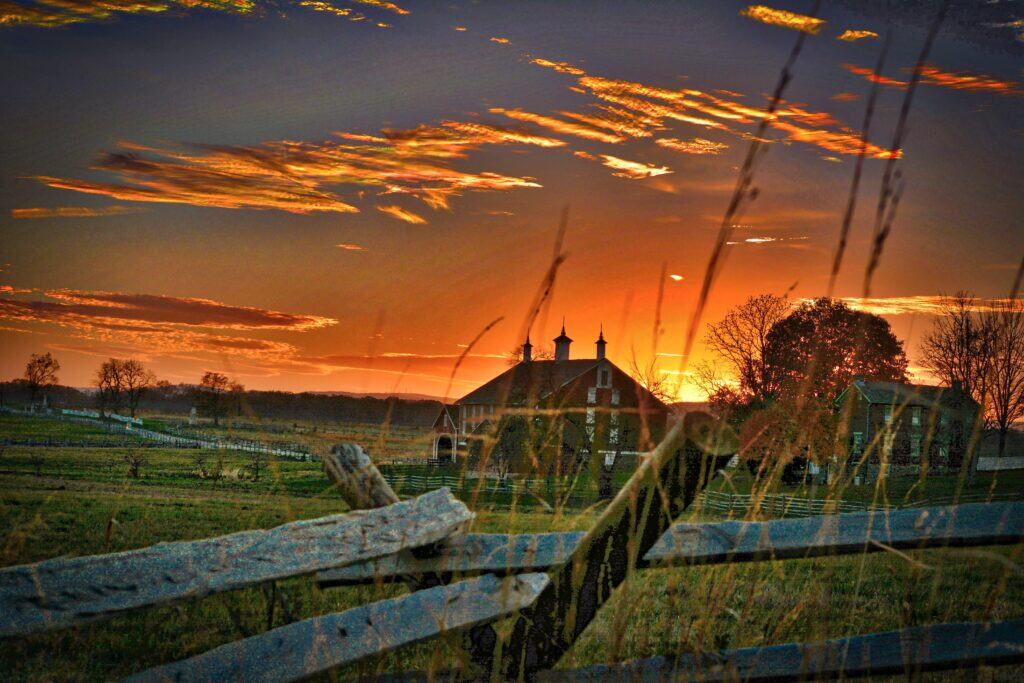

Gettysburg

The prolific traveler behind the massive repository of dark tourism destinations, dark-tourism.com, doesn’t think most battlefields qualify as dark tourism. In fairness, many are now just open fields. But I think that Gettysburg—where, during the 1863 Battle of Gettysburg, the casualties exceeded 50,000—does indeed count.

Exhibits and experiences at Gettysburg National Military Park expose visitors to the realities of war. Additionally, Gettysburg is a small town, and the bloodshed just 162 years ago overwhelmed the community, forcing it to build makeshift hospitals and morgues and bury thousands of bodies after the troops moved on. You can learn about the struggles faced by common soldiers, including their heroic deeds, at the military park and other Gettysburg destinations, while also gaining insight into Gettysburg civilian life at sites like the Shriver House Museum.

Johnstown

Western Pennsylvania’s Johnstown is the site of one of the worst disasters to befall the United States—and what’s worse, the catastrophe wasn’t entirely natural. In 1889, the South Fork Dam above Johnstown collapsed, and 20 million tons of water rushed toward the villages and town below. Almost the entire area was annihilated, and more than 2,200 people were killed. Heavy rains had directly triggered the dam’s failure, but the dam’s efficacy had been slowly eroded in order to provide a fishing lake and wide carriage road for the Pittsburgh industrialists—Andrew Carnegie, Henry Frick, and the like—who frequented the exclusive South Fork Fishing and Hunting Club that owned the dam.

A visit to Johnstown, including the Johnstown Flood National Memorial and the Johnstown Flood Museum, is both a sobering experience as one considers the loss of life and a maddening one when reflecting on the injustice of the flood.

Eastern State Penitentiary – Philadelphia

Eastern State Penitentiary is one of the most famous prisons in the United States. Intended to be a more rehabilitative form of incarceration from its start in 1829, the penitentiary instead inflicted severe psychological consequences on prisoners with its methods of solitary confinement and brutal disciplinary tactics. When Charles Dickens visited the prison in 1842—it was a tourist destination even then—he wrote of the “immense amount of torture and agony” that he witnessed.

The prison closed its doors in 1971, and today, Eastern State operates as a museum dedicated to preserving the prison’s tragic history and advocating for criminal justice reform, modeling the best form of dark tourism.

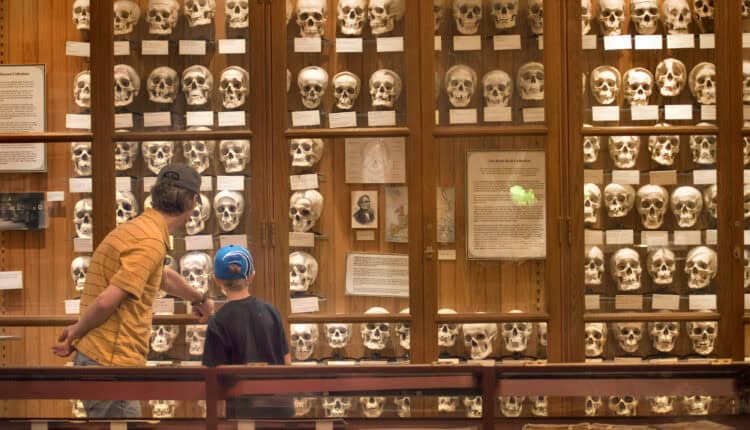

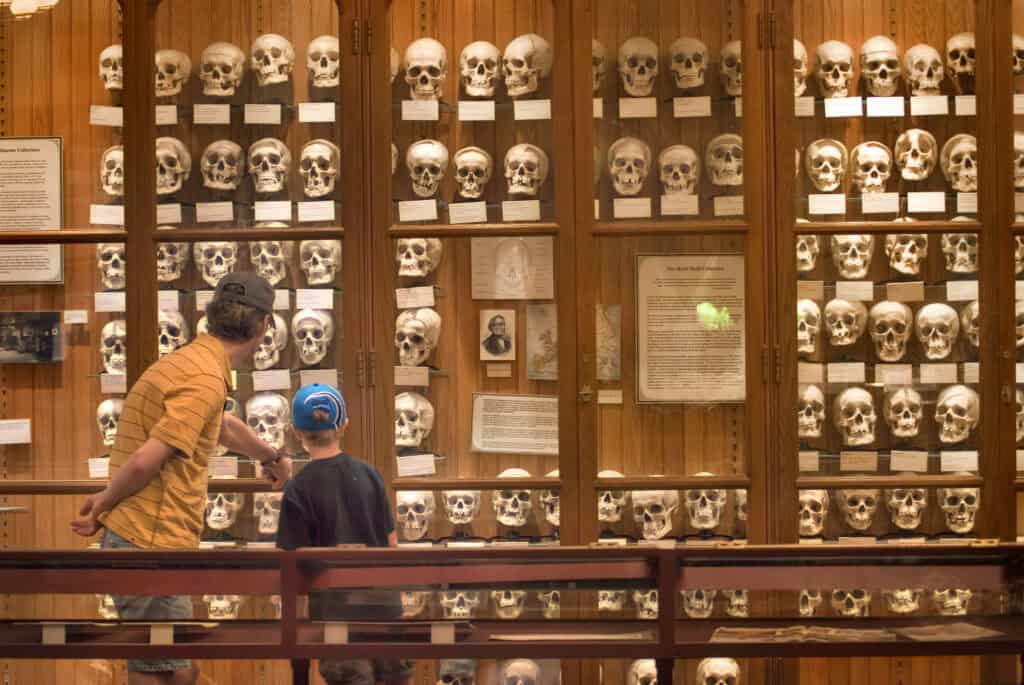

The Mütter Museum – Philadelphia

Since it first opened in 1863, Philadelphia’s Mütter Museum has focused on the history of medicine. It documents medical advancements as well as the more questionable procedures doctors of the past used to diagnose and treat illnesses. In order to best present this history, the museum also has a large collection of real human remains, from Grover Cleveland’s malignant jaw tumor to a woman whose body was essentially mummified when a chemical process caused a fatty, soap-like substance to encase her remains.

Ethics, as you might guess, can get dicey when a museum has, for example, an actual wall of skulls. Just last month, the museum announced a new approach to dealing with human remains, and it is now aiming to provide additional context and historical details for the displayed remains.

The Old Jail Museum – Jim Thorpe

Being sites of incarceration and maltreatment, prisons are often dark tourism subjects, and the Old Jail Museum in Jim Thorpe is no exception. The museum helps to expose the grim realities of imprisonment, particularly in the late 1800s and early 1900s, as well as the injustices of wrongful imprisonment and execution.

The jail opened in 1870 and served as Carbon County’s jail until 1995. But the jail is most famous for its association with the Irish labor group the Molly Maguires, and the unconstitutional trials by a coal company that brought seven Irish immigrant miners to their deaths at the jail’s gallows in 1877.

You can book guided tours of the old jail to learn more about the history and see the cells that once housed prisoners.

Austin Dam Remains – Austin

In Potter County, you can explore the remains of a paper mill’s dam that failed in 1911, leading to devastation in the town below.

The Austin Dam was designed to be safer than it ultimately was, but cost-cutting by the Bayless Pulp and Paper Mill eliminated some safeguards in the final product. Built in December 1909, the dam didn’t last two years before it burst. Nearby, Austin Dam Memorial Park honors the 78 victims of the disaster.

Pennhurst – Spring City

Pennhurst State School and Hospital was a state-run institution for mentally and physically disabled people that operated in Chester County between 1908 and 1987. Pennhurst’s overcrowded and abusive conditions spurred a landmark legal battle that galvanized the disability rights movement and resulted in the institution’s closure.

However, the building has since reopened as a haunted Halloween attraction called Pennhurst Asylum, and unless you’re careful, a visit may be an example of dark tourism gone wrong—the sort of voyeuristic and exploitative experience that dark tourism detractors warn against. When the haunted attraction first opened in 2010, the CEO of disability advocacy group The Arc urged people to boycott it, saying it “exploits the suffering that took place [at Pennhurst] and undermines meaningful efforts to eradicate stereotypes and negative perceptions that persist in society against people with disabilities.”

Since new owners took over in 2016, the site has expanded its historical offerings and attempted to separate them from the haunted attraction. It even offers tours led by professional historians. But the venture’s website still leans into the institution’s disability legacy for the Halloween haunt, promising the attraction “will push you to the limits of your sanity!”