Philadelphia’s Black Founding Fathers fought for freedom during an era when it was routinely denied to Black people.

Usually, when Americans talk about the “Founding Fathers,” they’re referring to a familiar cast of colonial-era political leaders—like George Washington and Thomas Jefferson—who helped establish the United States through pivotal documents such as the Declaration of Independence and the U.S. Constitution.

But that definition is necessarily narrow. It leaves out Black leaders who, in the same era, were fighting for freedom and building community in a nation that denied them full citizenship.

In Philadelphia, a center of early American political life, Black Founding Fathers played a crucial role in shaping both the city and the United States itself. They built churches, mutual aid organizations, businesses, and abolitionist groups, creating space for the city’s Black community and laying the foundation for generations of activism. Many of these institutions still exist today.

Read on to explore the lives of these important Black Philadelphians, learn how their impact is still felt, and discover where in the city you can engage with their legacy.

Richard Allen

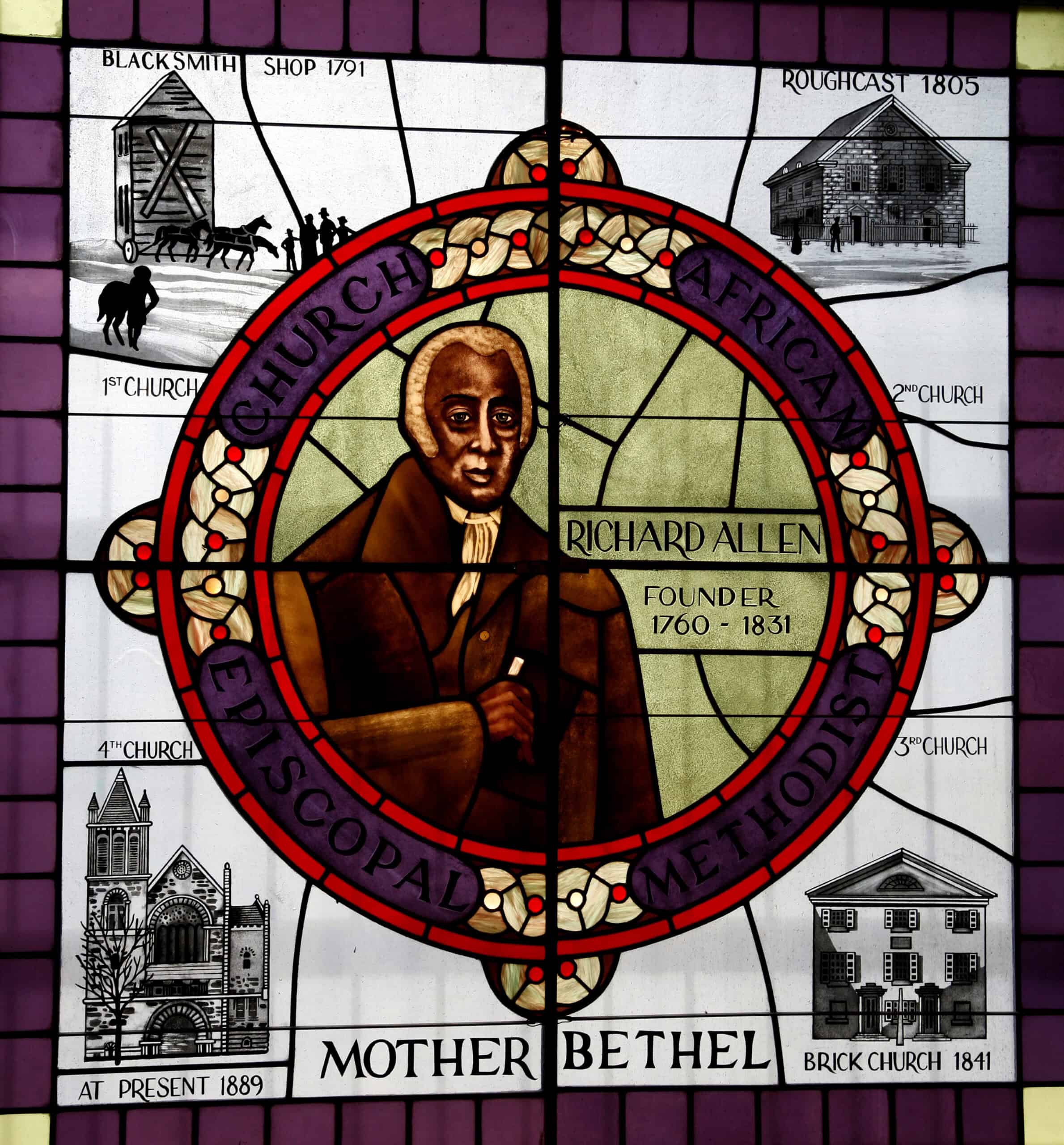

Born into slavery in 1760, Richard Allen purchased his own freedom, became a preacher, and founded the African Methodist Episcopal Church, the first independent Black Christian denomination in the United States.

After gaining his freedom, Allen moved to Philadelphia, where he began preaching at a segregated Methodist church. Sometime around 1787, after church leaders tried to further marginalize Black worshipers, he walked out along with fellow Black preacher Absalom Jones and other Black congregants. Soon after, Allen and Jones created the Free African Society, a mutual aid organization that supported newly freed people in the city.

In 1794, Allen founded Mother Bethel AME Church, which still stands on its original site in Society Hill as a center of Black community. It’s also the oldest Black-owned property in the country.

Frustrated by ongoing discrimination in the church, Allen ultimately broke from the Methodist Episcopal Church. In 1816, he helped unite five Black congregations in the Philadelphia area under the independent banner of the African Methodist Episcopal Church and was elected its first bishop.

Today, the AME Church has millions of members worldwide.

A 2008 biography of Allen, “Freedom’s Prophet: Bishop Richard Allen, the AME Church, and the Black Founding Fathers” by Richard S. Newman, details Allen’s life as a leading Black activist in Philadelphia who influenced generations of Black civic life.

Visit: Mother Bethel AME Church

Mother Bethel AME Church is not home only to its Sunday service, but also to the Richard Allen Museum. You can visit Allen’s tomb and also see church artifacts, like a ballot box used to elect church leaders in the 1800s and the original pulpit used by Allen. And be sure not to miss the church’s historic stained glass windows!

The museum is open on Sundays and the first Saturday of the month, as well as by appointment during the week. It’s also open every Saturday in February in celebration of Black History Month.

Absalom Jones

Like his contemporary Allen, Absalom Jones was born into slavery, later gained his freedom, and became a religious leader who preached both faith and abolition. Alongside Allen, Jones preached within the Methodist Episcopal Church but walked out when Black congregants were forced to worship in segregated seating.

Through his leadership in the Free African Society, the mutual aid organization he and Allen founded, Jones was instrumental in responding to the yellow fever epidemic that plagued Philadelphia in 1793. While many doctors fled the city, the society coordinated care for the sick and burials for the dead.

But unlike Allen, Jones wanted to create a Black-led congregation within the Episcopal tradition. He helped establish the African Episcopal Church of St. Thomas in 1794, which grew out of the Free African Society and became a cornerstone of Philadelphia’s Black community. The church has remained part of the fabric of the city even as it moved locations over the centuries. Today, it can be found in Philadelphia’s Overbrook Farms neighborhood.

In 1802, Jones became the first Black person in the U.S. to be ordained as an Episcopal priest.

Jones’ ashes are entombed in a chapel at St. Thomas church, which is also home to a stained glass window featuring his likeness.

James Forten

James Forten was born to free parents in Philadelphia in 1766 and spent his life fighting for Black freedom in multiple ways. As a teenager, he joined the Revolutionary War effort—sailing on privateer ships, he was captured as a prisoner of war by the British. Not long after returning to Philadelphia, he began apprenticing for a sailmaker and eventually bought the business.

Forten’s entrepreneurial skills saw him become one of the wealthiest men in Philadelphia, and he used his resources to fund anti-slavery causes, including abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison’s newspaper “The Liberator.” He wrote and spoke extensively against slavery and was closely connected to Black activists in the Free African Society.

In 2023, the Museum of the American Revolution hosted a special exhibit, “Black Founders: The Forten Family of Philadelphia,” on Forten and his family. You can still experience it by way of a virtual tour.

Cyrus Bustill

Cyrus Bustill was born into slavery in 1732, purchased his freedom, and was one of at least 5,000 Black soldiers who joined the Continental Army during the Revolutionary War. He served as a baker for the troops.

After the war, Bustill became active in Philadelphia civic life and was a founding member of the Free African Society. Because many Black Philadelphians were denied a formal education, Bustill opened his own school for Black children in 1803, operating from within his Third Street home.

James “Oronoco” Dexter

James “Oronoco” Dexter was formerly enslaved but gained his freedom and worked as a coachman in Philadelphia in the late 1700s. He lived with his family in a house now occupied by the campus of the National Constitution Center, where archeological excavations have unearthed key insights into everyday life in early Philadelphia.

While relatively little is known about Dexter’s life, records show he was active in the city’s Black community. He was one of the founding members of the African Episcopal Church of St. Thomas and hosted planning meetings at his home. He also signed what was likely the first draft petition to the federal government calling for the emancipation of enslaved people.

Visit: The Black Journey walking tours

While we’ve highlighted several influential Black Philadelphians, there are countless more who helped shape the city. Check out The Black Journey walking tours to explore the history of Black Philadelphia on the streets of the city itself. The Original Black History Tour dives deep into the early days of the nation, the contradictions between slavery and U.S. freedom, and the Black leaders who helped build the Philadelphia we know today.