Fascinating facts from New Hampshire’s Covered Bridge expert

Fall is the best time to check out New Hampshire’s covered bridges. Here are some fascinating facts from the state’s expert on the subject.

When is a New Hampshire covered bridge no longer just a covered bridge in New Hampshire? When it becomes an object of obsession. At least that’s what it is for Kim Varney Chandler of Hancock, who has spent years researching, photographing, and doing deep dives into the stories of these iconic wooden structures that dot the state, evoking devotion in those who visit and live here.

Chandler, a University of New Hampshire graduate and a full-time high school counselor, needed only to look around her own neighborhood to happen upon her obsession with New Hampshire’s covered bridges.

“I loved the covered bridge in my town, the Hancock-Greenfield or County Bridge,” she shared. “My husband, Marshell, and our dog, Pemi, would kayak under it when we moved back to New Hampshire. I wanted to know who built the bridge, when it was built, and who traveled over it. And that was it. I set out to visit every covered bridge in the state, photograph them, and learn their stories and the stories of the communities around them.”

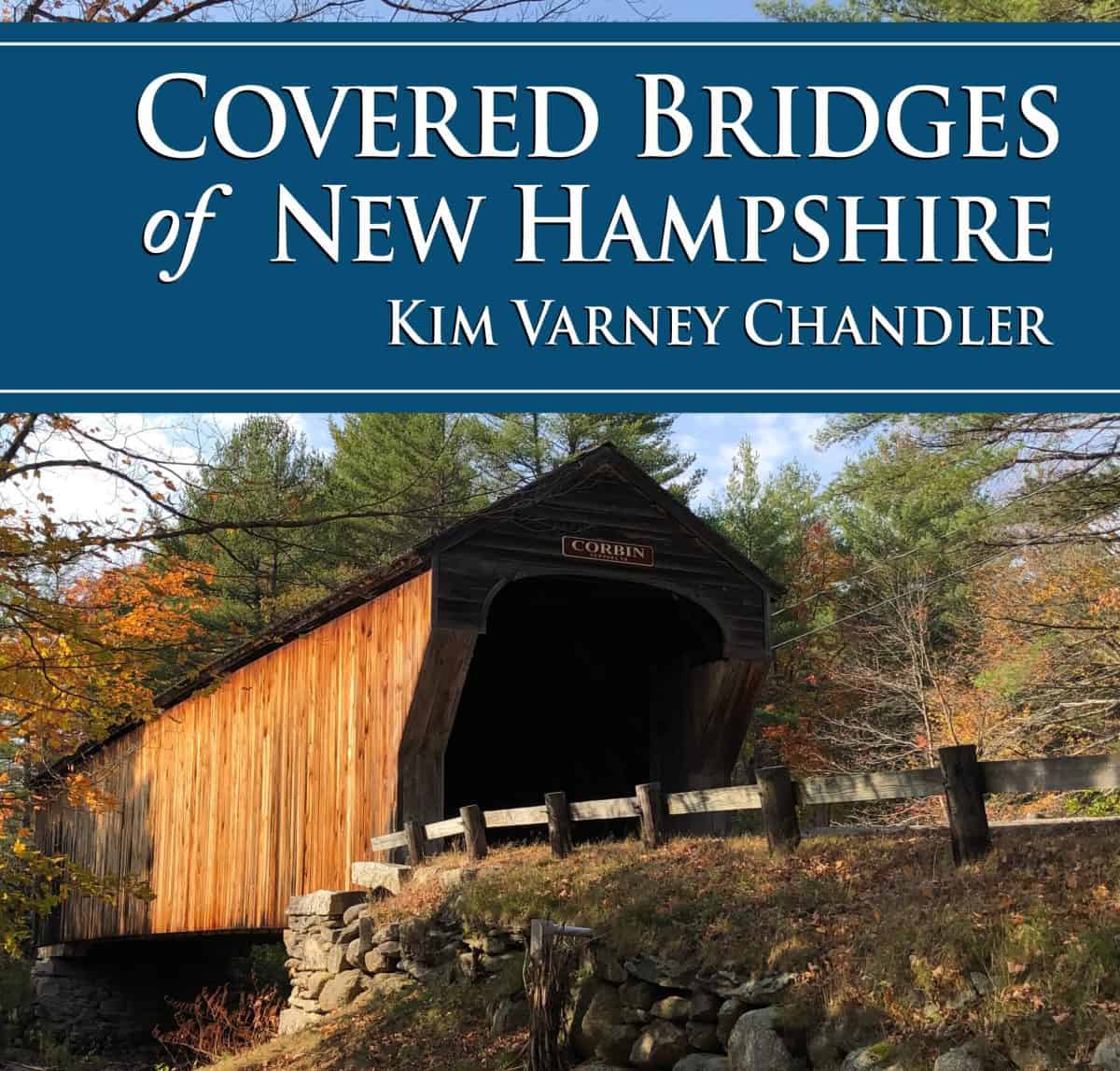

That goal resulted in the 2022 publication of Chandler’s 288-page photo-illustrated book, “Covered Bridges of New Hampshire,” a position on the New Hampshire Humanities Speakers’ Bureau, a blog, television appearances, and the Covered Bridges of New Hampshire Podcast.

Chandler also feels strongly that her New Hampshire covered bridge mission hasn’t been a solo effort. “When I was researching this project, literally 200 people helped me. Any community that had a bridge, town halls, libraries, historical societies, and preservation organizations heard from me. I talked to bridgewrights, timber farmers, engineers, and the people who support the preservation of the bridges in our state and don’t want to see steel and concrete structures replacing them. It was a collaboration.”

Fall is the best time of year to hit the road and take in the beauty of New Hampshire’s covered bridges, and there’s no one better to take along on the trip than our state’s covered bridge expert to offer fun facts about these cherished structures.

At one time, there were about 400 covered bridges in New Hampshire. Today, there are just 70 remaining: 58 have designated numbers, while the others do not. Chandler said she has been trying to verify which is the oldest covered bridge still in existence in the state, but with some difficulty. “There isn’t a lot of documentation,” she explained. “Part of the challenge is that you’ll see signs, like on the Swanzey Bridge, that say it was built in 1789, but that was the date of the original bridge that was built there. The one that’s there now was built in 1869. Right now, it seems like the oldest existing bridge is the Haverhill-Bath (Woodsville) Bridge, spanning the Ammonoosuc River, which was built nearly two centuries ago in 1829.”

Chandler also said many of the state’s original covered bridges burned down, were flooded out, or collapsed from the weight of heavy ice.

What’s in a name?

Many of New Hampshire’s covered bridges have two or more names, some of which stand out as whimsical. The Honeymoon Bridge (also known as the Jackson Bridge) in Jackson was built in 1876, one of the few surviving examples of a Paddleford truss bridge. It is said to have gotten its nickname from a New Hampshire historian who, in the 1930s, wrote about meeting his bride-to-be at the spot, said Chandler. She said each year the town holds a dance party at the structure.

There are several theories about how the 1869 Happy Corner (Hills Road, Perry Stream) Bridge, in Pittsburgh, got its name, said Chandler. One popular theory is that an elderly man living near the bridge owned an early record player and would invite neighbors over for song and dance sessions, or “happy time” parties, and the area became known as Happy Corner. But Chandler uncovered other theories in her conversations with townspeople. “When I was giving a presentation in Colbrook, one of the residents said the Happy Corner got its name because that was where some locals went with liquor and [sex workers] back in the day.”

The Blow-Me-Down-Bridge in Cornish, also called Squag City Bridge, Bayliss Bridge, Gorge Bridge, Freeman’s Mill Bridge, was built in 1877. It gets its name from the Blow-Me-Down Brook it spans. No one is sure how the brook, which was said to be discovered by a surveyor in the 1750s, actually got its nautical name.

Bridging history

The Dalton Covered Bridge in Warner, one of Chandler’s favorites, is believed to be the only covered bridge named after a woman: The widow Judith Sawyer Hoyt Dalton, who bought the property on Joppa Road after her second husband died. The 77-foot single-span truss bridge was built over the Warner River in 1853 for $980.12, after the town voted for the construction of a new “good bridge near Mrs. Dalton’s property, in the place of the previous bridge that had been carried away,” according to Chandler’s podcast. Since then, it’s been called the Dalton and sometimes the Joppa Road Bridge. The widow Dalton died three years after the bridge was built at the age of 92.

Chandler also likes to point out how a covered bridge in Sandwich not only spans the Cold River but also connects New Hampshire to an essential part of American history. The Durgin Bridge, originally built in 1869, just five years after the Civil War ended, was named for James Durgin and his wife, Jane Varney Durgin (a distant ancestor of Chandler’s) moved to Sandwich in the 1850s. Durgin worked as a stagecoach driver and, in Chandler’s words, “is believed to have been a ‘conductor’ on the Underground Railroad.” The Durgin family was believed to have hidden runaway slaves on their way north to freedom in their home, near where the bridge is now located.

Superlative New Hampshire

There are seven historic covered railroad bridges in the world, and New Hampshire is home to five of them. Pier Bridge and Wright’s Bridge, both in Newport, Contoocook Railroad Bridge in Hopkinton, Waterloo Bridge in Warner, and Sawyer’s Bridge in Swanzey.

Clark’s Trading Post Bridge in Lincoln, built in 1904 over the Pemigewasset River, is the only covered railroad bridge still in active use. And yes, it’s the bridge where the Wolfman chases trains at this iconic New Hampshire attraction.

At 228 feet, the Pier/Chandler Station Bridge, built in 1907 and spanning the Sugar River in Newport, is the longest existing covered railroad bridge in the world.

At 460 feet, the 1866 Cornish-Windsor Bridge, crossing the Connecticut River from Cornish to Windsor, Vermont, is the longest wooden bridge in the United States and the longest two-span covered bridge in the world. The first is in Lucerne, Switzerland.

Woo woo?

It being spooky season and all, we had to ask Chandler if any of New Hampshire’s historic covered bridges are haunted. “I don’t know about that,” she said. “No one’s told me they’ve seen any ghosts on bridges. But there have been stories about the Blair Bridge in Campton.” The current structure on the spot was built in 1870, crossing the Pemigewasset River. But it replaced the previous structure built in 1829. According to some historical records, it was burned down by Lemuel Palmer, a Civil War veteran charged with arson after he drove his horse-drawn hay wagon on the bridge, lit the hay on fire, then unhitched the animal. He claimed at the trial that the voice of God told him to do it. He was found not guilty.